Recoil is a necessary evil. It is unavoidable and can make shooting a gun intimidating. The larger the caliber you are shooting, the more you have to deal with. Although it is inevitable, there are things that you can do to mitigate it. Adding a recoil pad, installing a muzzle brake, and using a suppressor will all help reduce recoil. All of these options have advantages and disadvantages, and no one way is best for everyone.

Affiliate Disclosure: This article may contain affiliate links. When you use these links, I earn a small commission from each sale generated at no cost to you. This commission helps me continue to put out free content. I work a full-time job that I am very happy with; therefore, I don’t need this commission and am not obligated to speak highly of any product. Everything written is my own opinion: the good, the bad, and the ugly.

What is Recoil?

Recoil is a mechanical function of Newton’s third law; for every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction. The action, in this case, is the cartridge firing and the projectile’s movement. Reaction, combined with a few other factors, is the gun’s recoil or rearward thrust.

There are two numbers that we will be referring to regarding recoil to help better understand it. The first is recoil energy, which is measured in ft-lbs. The second is recoil velocity, which is measured in feet-per-second(fps).

Recoil Energy and Velocity

Recoil energy is the total amount of recoil that will be transferred to the shooter while firing a gun. The higher amount of energy, the more recoil that is felt. It is often referred to as “Free Recoil” as it refers to the amount of energy when it is facing no resistance. However, there is no better way to represent this as everything beyond that is subject to the shooter. The last thing we want is a more complicated formula where we are entering body mass index!

Recoil velocity is a number that represents how fast that energy is being transmitted to your body. The higher the velocity, the sharper the recoil will be. Yes, much more goes into felt recoil than those two things; however, this is the best way to represent them numerically.

To keep it as simple as possible, throughout this article, we will use numbers that reflect a manually operated rifle or pistol. Single shots, lever, pump, and bolt actions are examples of manually operated firearms. By manually operated, I mean that the shooter has to load and unload each cartridge and that recoil and/or gases are not used to operate the firearm. While the principles of reducing recoil will be the same, it is much more complicated as the weights of the individual moving parts play a large role in its function.

Related article: Blowback Operated Guns: Way More Than You Need To Know

The Three Elements of Recoil

Recoil as a whole can’t be attributed to a single thing. It is a combination of multiple phases of the rifle firing. General Julian S. Hatcher studied recoil very heavily and has broken it down into three different elements. Personally, I have found no better explanation of this anywhere else. More information on these three elements can be found in his book, Hatcher’s Notebook.

The first element has to do with the reaction that accompanies the bullet’s acceleration as it moves down the barrel. Or how much energy it takes the bullet, at a state of rest, to reach its muzzle velocity.

The second element is the reaction that accompanies the acceleration of the powder charge. This is in the form of the gas that is created by the combustion of the powder.

The third element is the reaction due to the muzzle blast, which occurs when the bullet leaves the muzzle and releases the gases mentioned in the second element. Hatcher compares this element to the type of reaction that propels a rocket.

Thinking about recoil in these three elements really help you understand the formula associated with it. It also helps with understanding how to mitigate it.

How to Calculate Recoil Energy

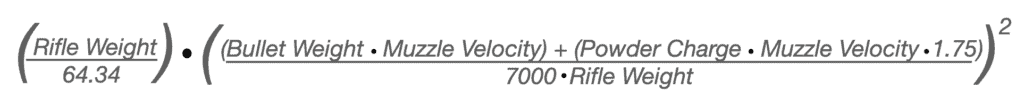

The formula for recoil is a lot easier to calculate than it looks. It’s relatively simple but requires you to know your powder charge weight. While most handloaders know this number, those who don’t will have trouble getting an accurate calculation. The second part of the equation refers to the recoil velocity.

There are only four numbers that you need to know to calculate this equation; rifle weight(lbs), muzzle velocity(fps), bullet weight(gr), and powder charge(gr). Below, I ran the calculation for my hunting rifle chambered in 270 Winchester. The numbers represent some of the loads that I had initially tested for accuracy. The top load, shooting the 130 gr Barnes TTSX bullet at 2,800 fps, was the most accurate and is what I hunt with. This rifle has a relatively short-for-caliber 22-inch barrel.

In 1909, the British Textbook of Small Arms identified that 15 ft-lbs of recoil energy was the maximum allowable for a military service rifle. This is still largely accepted as the standard for comfort. While military shooters are expected to shoot much more than the average sportsman or woman, the farther you stray away from that 15 ft-lbs number, the more likely you are to develop a flinch. According to Chuck Hawks, most shooters will develop a serious flinch with recoil energy over 20 ft-lbs. (Chuck hawks has a great table that includes a variety of calibers and their associated numbers. It can be found here.)

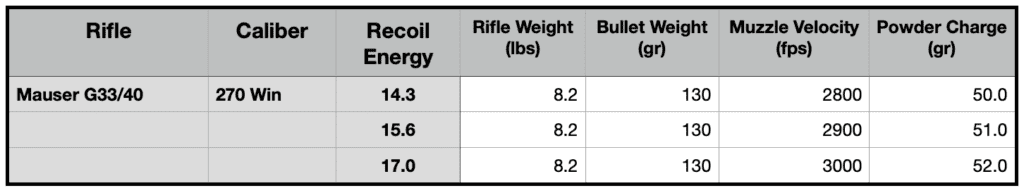

Recoil Velocity and How it Affects the Shooter

Recoil velocity is how fast that energy is transmitted to the shooter. It also happens to be the second half of the equation used to calculate recoil energy, meaning it has a direct effect. The higher the recoil velocity, the sharper or harsher the recoil feels. That initial impulse is physical and, to an extent, psychological.

In 1929, the Brits updated their British Textbook of Small Arms to state:

“As regards to sensation of recoil, it seems well established that the actual velocity of recoil is a very great factor. In shotguns weighing six to seven pounds, 15 fps has been long established as a maximum above which a gun-headache is sure to ensue. But with an elephant rifle weighing perhaps fifteen pounds, such a velocity is unbearable for more than one or two shots.”

I find that 15 fps is an excellent number to go by for a general hunting load. For dangerous game, it is virtually impossible to stay under that number.

What Makes Recoil Worse?

There are many factors that will increase recoil. As you can expect, they are all directly correlated to the recoil energy formula. Rifle and bullet weight, bullet velocity, and powder charge weight.

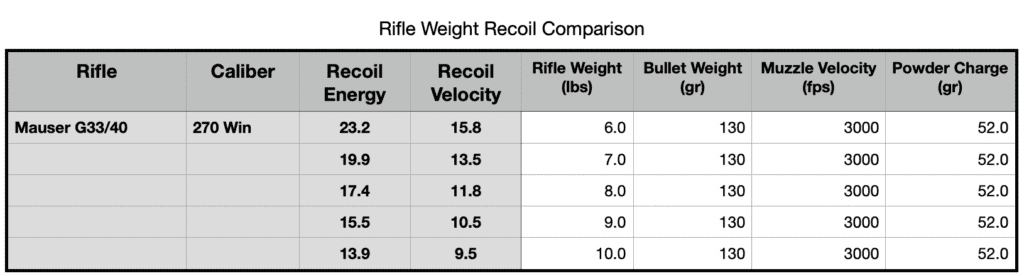

Reduced Rifle Weight

The weight of the rifle is the biggest contributing factor to felt recoil. In fact, it shares a direct relationship with it. If you reduce a rifle’s weight by 10 percent, you’ll increase the recoil by approximately the same amount. This is a no-brainer but also the hardest one to overcome for the hunter. Everyone, including myself, wants a lighter rifle to carry, but is it worth the increased recoil and possibility of developing a flinch?

In his legendary book, Hatcher’s Notebook, General Julian S. Hatcher writes:

“We know from experience that a heavy gun kicks less than a light one; both that and calculations show that with a given bullet weight, powder charge and muzzle velocity, the energy of free recoil is inversely proportional to the weight of the gun; that is, a gun weighing twice as much would have half the recoil.”

Changing the rifle’s weight is also one of the most labor-intensive methods of effecting recoil. That usually means changing out the stock or taking it to a gunsmith to get a lighter barrel put on. Therefore, I consider this area to be one that you are somewhat stuck with unless you are willing to make the investment in time and money.

Increased Bullet Weight

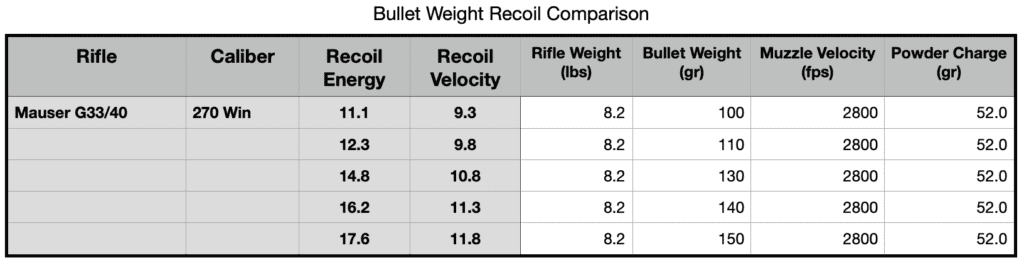

Again, using my 270 Winchester example, we look at the effect bullet weight has on recoil. It isn’t hard to imagine that increasing the bullet weight will increase the recoil, but how much? And what are the downsides to going this route? “How much” is hard to put a number on, but in this case, assuming velocity is kept the same, increasing the bullet weight by 50-grains will increase the recoil energy by 6.5 ft-lbs.

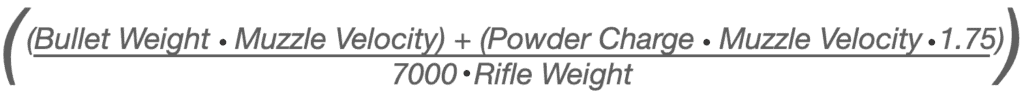

Increased Muzzle Velocity

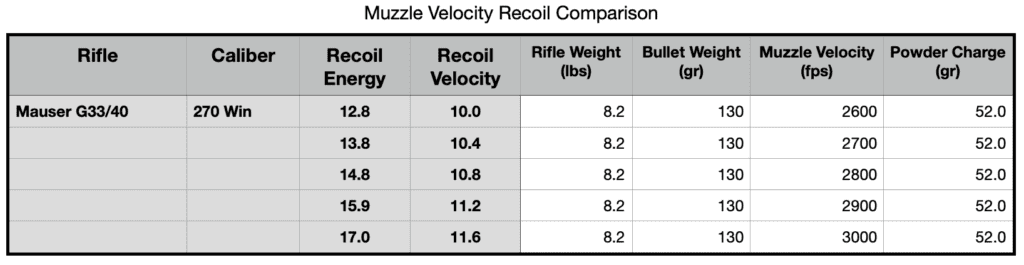

Higher Velocities also attribute to more felt recoil. If we assume all else is equal, increasing the muzzle velocity of your rifle will increase the recoil. In most cases, the powder charge will also increase with the increase of muzzle velocities. However, it is possible to have the same powder charge weight and get different velocities using different powders. For example, according to Hornady’s Handbook of Cartridge Reloading, 48.6 grains of IMR 4064 powder will shoot a 130-grain bullet at 3,000 fps, while 48.6 grains of Win 760 powder will only reach 2,700 fps.

Powder Charge Weight

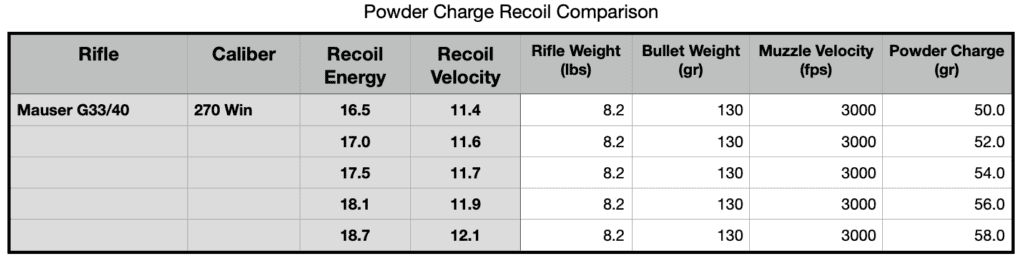

Just like the effect of higher velocities, the weight of your powder charge will affect felt recoil. As you can see in the above chart, it is possible to reduce the recoil of my 270 Winchester by 2.2 ft-lbs just by choosing a more efficient powder! The downside is that powder type plays a big part in the accuracy of a rifle. The most efficient powder may not be the most accurate.

Ways to Reduce Recoil

As stated above, recoil is a constant number dictated by recoil energy and recoil velocity (bullet weight, muzzle velocity, powder charge weight, rifle weight). How recoil is perceived and felt is different for every shooter. This perception of recoil is related to the body’s deceleration against a firing gun.

A shooter will always feel less recoil when shooting off-hand instead of prone. However, the actual recoil remains the same in this scenario. Your body absorbs the recoil over a longer period of time when standing, reducing that initial impulse.

Perceived recoil is different for each shooter. A 200-pound, 6-foot tall person will perceive shooting an eight-pound 30-06 Govt’ rifle differently than a 140-pound, 5-foot tall individual. This perceived recoil can be reduced using several different methods not previously mentioned.

Recoil Pads

Recoil pads are one of the best ways to tame recoil and have become the standard on most guns manufactured today. They effectively reduce the felt recoil in a number of ways. First, most rubber recoil pads do, in fact, weigh more than a steel buttplate. While this difference is only a matter of ounces, it does make a difference.

However, no one is adding a recoil pad because they want the extra weight. The recoil pad is made out of soft rubber or sometimes foam that helps absorb the initial shock of the recoil velocity. This essentially lengthens the amount of time it takes the recoil energy to reach your body. You are still absorbing all of the energy, just over a longer period of time.

There are many options for recoil pads, and some work better than others. For the most part, recoil pads are screwed to the back of the buttstock and used in that manner. Although, there are slip-on recoil pads that fit over the existing buttplate on your stock. The slip-on pads also allow you to get the benefit of recoil reduction without modifying your prized old gun. The downside is you will more than likely lengthen your rifle or shotgun’s length of pull by an inch or so.

There are pros and cons to both. First, recoil pads are ugly. Especially the slip-on ones. The only good-looking recoil pad, in my opinion, is made by Galazan and resembles the old Silvers red pads, but unfortunately, they are made of pretty hard rubber do little to reduce recoil. The best thing about recoil pads is that they are very affordable!

Use coupon code KTG10 to get 10% off your order of $150 or more at Brownells.

Muzzle Brakes

Muzzle brakes have grown in popularity over the past few years and now many factory rifles chambered for magnum cartridges come with them installed. They work in the third element of recoil by redirecting the gases that are exiting the muzzle.

The recoil reduction of a muzzle brake is incredible. While every design is different, a shooter can expect a 40-50% recoil reduction with a well-designed brake. They really are all they’re cracked up to be. It makes shooting heavy magnum cartridges relatively pleasant. However, they do have their downsides.

The biggest downside to a muzzle brake is the muzzle blast associated with them. Simply put, they are LOUD! Redirecting the gases comes at the price of your hearing. This isn’t much of an issue if primarily shooting at a range with ear protection. However, in the hunting world, this can make all the difference.

A muzzle brake can also negatively affect accuracy. Screwing it onto the end of your barrel can have an effect on the harmonics of the barrel, but the real issue has to do with the barrel threads. The threads on your barrel must be concentric to your bore to be as accurate as possible when using a muzzle brake. Choose your gunsmith wisely if having this work done.

A muzzle brake’s effect on accuracy could be a whole article in itself.

Suppressor

Yes, suppressors reduce recoil! Just like muzzle brakes, suppressors work in the third element of recoil. They do add a significant amount of weight to the end of the barrel, enough to reduce recoil in itself. But they also increase the amount of time that it takes for you to absorb the recoil energy, making for a softer feeling recoil. Dead Air Silencers actually makes an E-Brake attachment for their line of suppressors that reduces recoil even more than the suppressor itself.

In general, I personally don’t believe that suppressors are as effective as muzzle brakes at reducing recoil. But there is no ignoring their effectiveness. The barrier to entry is the biggest downside to using a suppressor for recoil reduction. The paperwork-laden process takes months to get approved and keeps a lot of people from buying them.

Just like muzzle brakes, suppressors’ weight and general design can negatively affect your rifle’s accuracy.

Recoil, Recoil, Recoil

Recoil is much more complicated than most believe. Unfortunately, it is a necessary evil in the world of firearms. I remember sitting at the shooting bench many years ago while sighting in my 30-06. My shoulder was becoming sore as I had issues getting it where I wanted, and I started dreading the shot. I can’t remember who said it, but it stuck with me forever. “Learn to Love it.” Learn to love it, I thought. Surprisingly, it worked. I do kind of like the abuse now. It is the trade-off for doing something that I enjoy so much.

While I have shown you a number of things that affect recoil, it is impossible to eliminate it entirely. Learn to love it.

Written by: Kurt Martonik

Kurt is a Gunsmith, Reloader, Hunter, and Outdoorsman. He grew up in Elk County, Pennsylvania, where he became obsessed with the world of firearms. Following high school, Kurt enlisted in the United States Air Force as a Boom Operator, where he eventually rose to the position of Instructor. After his military service, he attended the Colorado School of Trades(CST) in Lakewood, CO for gunsmithing. Following graduation, he accepted a job at C. Sharps Arms in Montana, where he worked as a full time stockmaker and gunsmith.